This past fall, I visited the Smithsonian National Museum of American History for the first time since I was a child. As a person who loves to cook and bake, I immediately fell in love with “Bon Appetit! Julia Child’s Kitchen,” an exhibit in which curators have reconstructed Julia Child’s Cambridge, MA kitchen inside of the Smithsonian. Originally, Child’s kitchen was designed to be a stand-alone exhibit (which opened on August 19, 2002), but because of its popularity, it has been incorporated into the museum’s current exhibit “FOOD: Transforming the American Table 1950-2000.” Once I discovered that the Smithsonian had created a digital companion site to go along with the physical exhibit, I decided to visit the physical site in D.C. again, but this time as a researcher, reviewing the interpretation, audience, layout and features, in order to compare them to the elements of the digital companion site. I have outlined what I discovered below.

Bon Appetit! Julia Child’s Kitchen – Physical Site

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Now part of the exhibit: “FOOD: Transforming the American Table 1950-2000”

One is first drawn to the physical site by viewing Julia’s kitchen through a glass door, which offers visitors a glimpse into the vibrant kitchen before even entering the exhibit proper. Because the kitchen is now just the first stop on the way into the larger “FOOD” exhibit, one must enter past the current exhibit sign and turn to the left, in order to view the glass-walled kitchen. Next to the kitchen is a hallway which leads to a second part of the exhibit which includes other items related to Julia’s life and a TV showing re-runs of her cooking shows. It is laid out well, with an inverse funnel-shaped hallway. This seemed to encourage visitors to first pass the kitchen on the left, and then move on to the display cases of additional artifacts and stories and finally encounter Julia on the TV screen, in one of her classic cooking shows. While there seems to be a suggested order to view the exhibit, it by no means has to be strictly followed; visitors are allowed to go at their own pace and in their own order.

The creators of Bon Appetit! seemed to have several interpretive points in this exhibit which they supported in a number of ways. In general, they wanted to showcase the life of Julia Child — educating the public about a woman who has been influential in American culinary and television history. The curators used this exhibit to show the roots of Julia’s cooking prowess and explain how she transformed American cooking by offering step-by-step directions. They also wanted to show the contributions she made in the evolution of TV cooking shows in America, culminating in the creation of the Food Network. To do this, they incorporated personal objects, such as photos of her cooking in her Paris kitchen, her diploma from cooking school, her Légion medal, and objects from her cooking shows, such as blow torches and large knives. They also placed a TV in the exhibit which showed examples of her cooking shows, displaying the knowledge, wit, humor, and personality which made her a star. They also placed Julia’s life and culinary career in the context of WWII, talking about her work for the OSS in Sri Lanka and China which exposed her to foreign cuisines.

The creators also used Julia’s kitchen as a case study in order to get visitors to think about kitchens as symbols of American life. They showed how new technologies helped to create a “modern kitchen” by pointing out items in Julia’s kitchen. For example, a mortar and pestle, a food processor, and a KitchenAid mixer showed the evolution of modern appliances. They also included a display which put the “modern kitchen” concept into the larger context of the 1950s and 60s, showing visitors how “modern kitchens” were depicted in popular magazines and at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York.

It is clear that the Smithsonian produced this exhibit to appeal to a wide range of audiences. It is attractive to many because kitchens and cooking food is something that (in one way or another) is common to the human experience. Personally, I think it would be particularly attractive to people who (like me) love to cook. Seeing all of the different kitchen appliances and tools was a joy. I imagine that others would enjoy comparing what Julia used to their own collection of implements and tools. Secondly, I think this exhibit would be particularly attractive to people who grew up watching Julia Child on TV or using her cookbook in their own kitchen. They would enjoy seeing her kitchen in person after seeing it on TV for many years.

When I was actually in the space, the present audience was very diverse. When I first entered the exhibit, there were five people (2 females, 3 males in their 30-50s) sitting and standing in front of the TV, watching one of Julia’s cooking shows. As I got closer, one of the females clapped her hands and commented “She (referring to Julia) is so smart! That is how you do it!” to which her companions laughed and smiled. Clearly they had been there awhile and were thoroughly enjoying themselves. In the next 10 minutes or so, visitors cycled in and out of the exhibit. There was a teenage girl and her dad, an African American couple, a Mom and Dad with their two young children, and a young couple in their 20s. The visitors were multi-ethnic and not all of them were speaking English. While the teenagers and children seemed to spend the majority of their time in the exhibit looking at the kitchen itself, the adults seemed to spend a longer time looking at the additional artifacts and watching Julia’s TV re-runs.

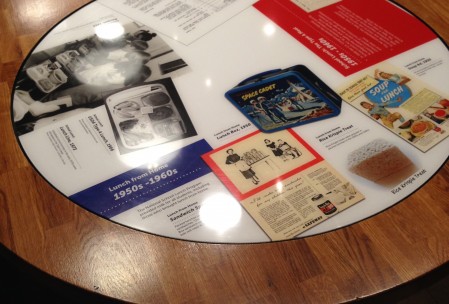

Even though the exhibit was rich in objects and content, it seemed to lacking in interactive elements and curators. While there were no interactive elements in Bon Appetit!, there were some spinning disks that were incorporated into the larger “FOOD” exhibit. During the time of my observation, children were using them simply as toys to spin, instead of tools to engage with the material written on them. I also found zero curators in the exhibit, although they were present in other exhibits in the museum. When they were present, they were standing by themselves and not interacting with visitors. They would answer questions if visitors approached them, but their main job seemed to be watching over the artifacts.

Even though the exhibit was rich in objects and content, it seemed to lacking in interactive elements and curators. While there were no interactive elements in Bon Appetit!, there were some spinning disks that were incorporated into the larger “FOOD” exhibit. During the time of my observation, children were using them simply as toys to spin, instead of tools to engage with the material written on them. I also found zero curators in the exhibit, although they were present in other exhibits in the museum. When they were present, they were standing by themselves and not interacting with visitors. They would answer questions if visitors approached them, but their main job seemed to be watching over the artifacts.

If I were re-designing this exhibit, I would change two things: one physical and one content-based. First of all, I would make sure to include more seating in front of the TV. Surprisingly, many people spent a long time watching Julia’s show. There was only one small bench available that would seat two people at most. Adding more seating would allow visitors to sit and enjoy the show for as long as they liked, instead of encouraging them to move on after a few minutes. Secondly, the Smithsonian recorded audio interviews with Julia Child and posted them online to a site called “What’s Cooking?” (I’ll talk more about this below). I am surprised that they did not incorporate them into the physical exhibit. I would include a computer station that would allow visitors to see transcripts of these interviews and even hear the interviews straight from Julia’s mouth by listening to audio recordings.

Bon Appetit! Julia Child’s Kitchen – Digital Site

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

http://amhistory.si.edu/juliachild/

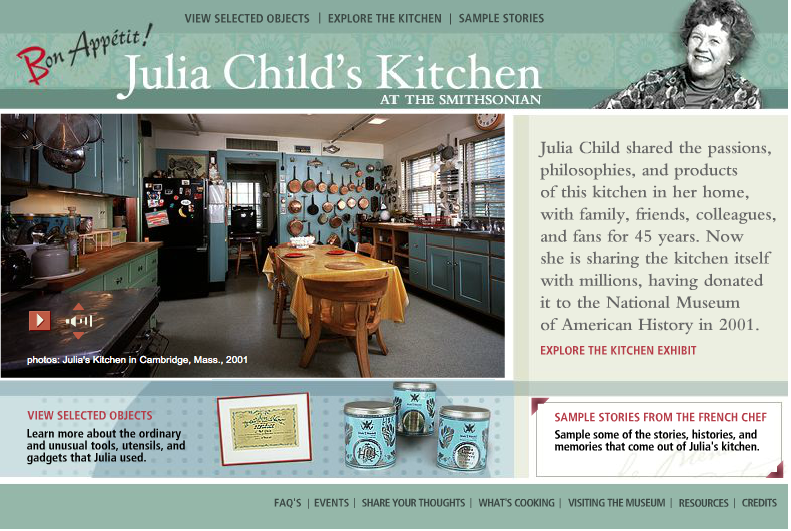

When you first enter the Bon Appetit! digital site, you are greeted with a voice-over from Julia Child, proclaiming how proud she is that the Smithsonian wanted her kitchen and that she was very happy to donate it. She donates in hopes that her kitchen might “influence anyone to go into the culinary profession as a career” and wants visitors to embrace the kitchen and “make it a real family room and part of your life.” This stirring and heartfelt introduction helps the visitor make an instant connection to Julia.

It seems that much like the physical site, the curators’ goal was to introduce Americans to the personal life of Julia Child, an important women who has shared her love for cooking with the American public for over 40 years though her cookbook and television cooking shows. Unlike the physical exhibit, the digital exhibit did not place Julia’s kitchen in the context of the “modern kitchen” or emphasis the evolution of kitchen technology. Instead, they focused on her objects and stories about her life.

The site design is very simple but organized. The main page cycles through several pictures of Julia’s actual kitchen in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 2001, before it was moved to the Smithsonian. It also has has three placards on the front page, inviting readers to “Explore the Kitchen Exhibit,” “View Selected Objects” and “Sample Stories From the French Chef.” These three links correspond to the three sections of the website. There are also links to these same three sections in a menu bar across the top of the window. The site does not encourage a single flow. Visitors are welcome to choose which of the three sections they would like to explore first by what appeals to them the most.

This site offers three main sections with different types of content. First of all, there is a section called “View selected objects.” This contains a collection of 66 objects featured in the physical exhibit such as one of her stock pots, a needlework sign that reads “Bon Appetit,” a kitchen scale, tea tins, a butcher knife, her Cordon Bleu Diploma, and a signal mirror from her days in the OSS during WWII. This section is obviously object based, but includes descriptive text as well. A second section called “Explore the Kitchen” showcases a panoramic image of Julia’s kitchen as it is set up in the Smithsonian. This is interactive, so that visitors can manipulate it to get a 360 degree view. The panorama also includes asterisks on certain items, which when clicked, yields greater information about the item or the layout of the kitchen. Finally, a third section, “Sample Stories,” contains a timeline of Julia’s life that visitors can scroll through horizontally. This timeline also includes links to 18 stories about her life, presented in text and photographs. Some stories are linked or related to specific artifacts in the online collection. These stories really flesh out the personal information about Julia and give the visitors a personal connection. Through the stories, visitors learn about the impact of WWII in her life, her husband Paul, her time at the Cordon Bleu cooking school in Paris, her rise to TV fame with her cooking shows and her donation of her Cambridge kitchen to the Smithsonian in 2001.

The digital site’s intended audience seemed to be just as general as that of the physical site. As I said before, I think people who enjoy cooking or grew up with Julia Child would be most interested in the site. For these audiences, the digital site is great. For cooking enthusiasts, it provides a close-up of kitchen objects and a panorama of the kitchen. For people who are familiar with Julia’s TV shows or cookbook, the timeline and stories provide further detail into her personal life and cooking roots. My only criticism, is that the site assumes that one already knows who Julia Child is and why it would be a great accomplishment to preserve her kitchen. The home screen does not explain that she was a great cook, a cook book author, or even a TV cooking show host. It simply says that she has “shared the passions, philosophies, and products of this kitchen in her home, with family, friends, colleagues, and fans for 45 years.”

Finally there are (at least by 2016) few participatory activities or ability to interact with the site’s creators. There is one “interactive” element: the panorama. But that only allows visitors to drag it around on their own terms. It does not allow them to add anything to the site. At one point, it seems that the site allowed visitors to submit comments, but that has now been closed. They do include three of the comments visitors submitted, including one from a friend of Julia’s who shared her own engaging story about Julia. If I were in charge of the site, I would have included more comments like these, especially ones from people who know Julia personally. Reading other visitors’ comments or stories and then being able to submit your own can trigger one’s own recollections and form lasting memories from the site.

In addition, there was no option for visitors to directly interact with the site creators. Nevertheless, they did include a link to a companion site called “What’s Cooking? Julia Child’s Kitchen at the Smithsonian.” (http://www.americanhistory.si.edu/kitchen) This separate site documents the year-long process of acquiring Julia’s kitchen, cataloging it, and reconstructing it at the Smithsonian through a project diary. Even though visitors can’t be in direct dialogue with the curators, this alternative site gives visitors insight into the process the creators went through to develop both the physical and digital sites. It also includes audio files and transcripts of 16 interviews they conducted with Child. They also seem to have taken videos of Child in her kitchen when they went to deconstruct it in 2001 (although these are not displayed on the site). With the new trend toward oral history, I am again surprised that they did not include audio and textual versions of these interviews, as well as the video clips in the physical exhibit and especially, in the digital site.

If I were to change the digital site, I would add in some of the context that is present in the physical exhibit. I would connect Julia’s kitchen to the concept of “modern kitchens” and ask visitors to think about how similar or not similar her kitchen was to the ones showcased in popular magazines. I would also definitely include all audio clips and videos available to me. Hearing someone’s voice always forms a stronger personal connection than reading words that someone has written. Lastly, I am surprised that the site contained none of Julia’s recipes or cooking methods. If possible, I would include a few of her most famous recipes.

Comparison

The best part of the physical exhibit for me was the objects — especially the completely reconstructed kitchen. Standing in Julia’s kitchen and being surrounded by authentic pieces which were arranged exactly how Julia left them is an incredibly moving experience. While the digital site shows the kitchen through an interactive panorama and presents 66 other objects individually, it can never compare to the emotional connection that is created by seeing the objects and kitchen in person.

The best aspects of the digital site were the accessibility and additional behind-the-scenes information shared on the “What’s Cooking” companion site. First of all, as with any online project, the digital version of Julia’s kitchen makes the exhibit accessible to people around the world. This is important since many Americans are not physically or financially able to come and see the exhibit in person in Washington, D.C. Creating an online exhibit makes access more fair. Secondly, the best part of the digital exhibit was not the site itself, but the companion site which explained the process that the curators went through to produce the exhibit. This site also included wonderful audio interviews with Child, which (I think) should have been included in both the physical and digital site. In general, I enjoyed both versions. I think they both brought something unique to the table while still using the same objects to present two very similar stories.

*All photographs of the physical exhibit taken by the author on a recent trip to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.