Co-written with Caroline Greer and originally posted on the blog for the American Religious Ecologies project. Read the the original post here.

As mentioned in our previous post, one of the fascinating aspects of the 1926 Census of Religious Bodies schedules is the information they provide about individual congregations—details about the congregation’s finances, educational activities, physical location, the make-up of their membership, and the education of their pastorate. Nevertheless, the schedules leave much to be desired when trying to understand a congregation’s charitable activity. The Census Bureau, in fact, only asked one question in this area: the amount of money expended by the congregation on benevolences, including foreign and domestic mission work, in the past fiscal year.

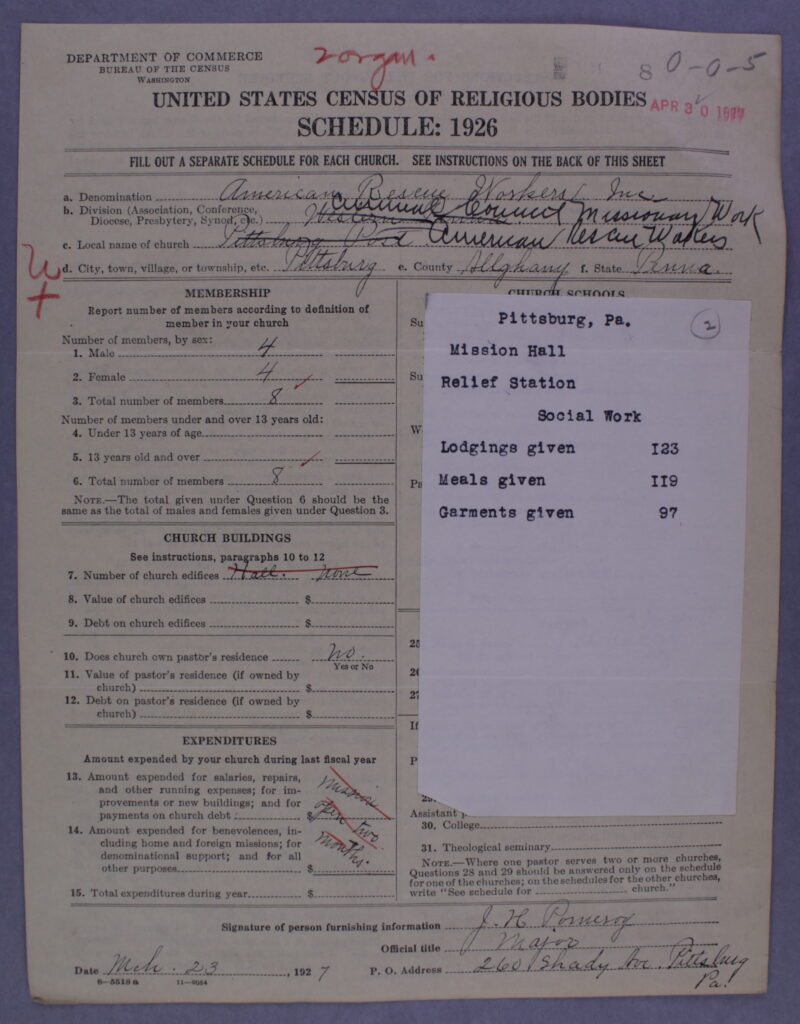

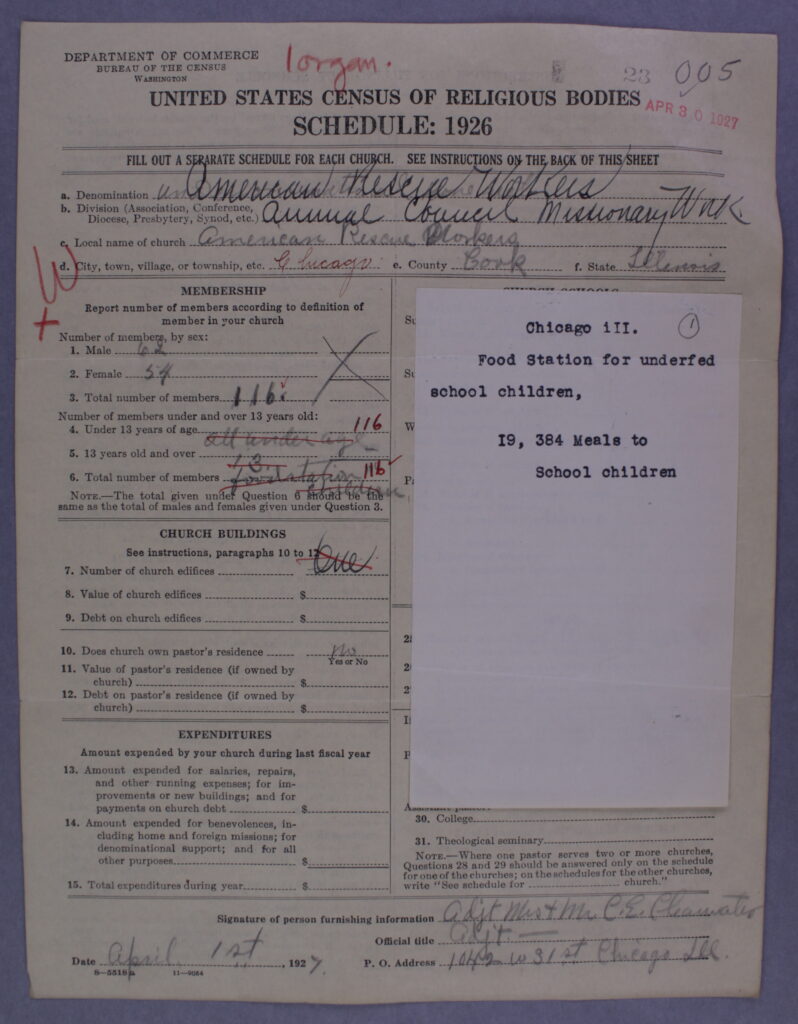

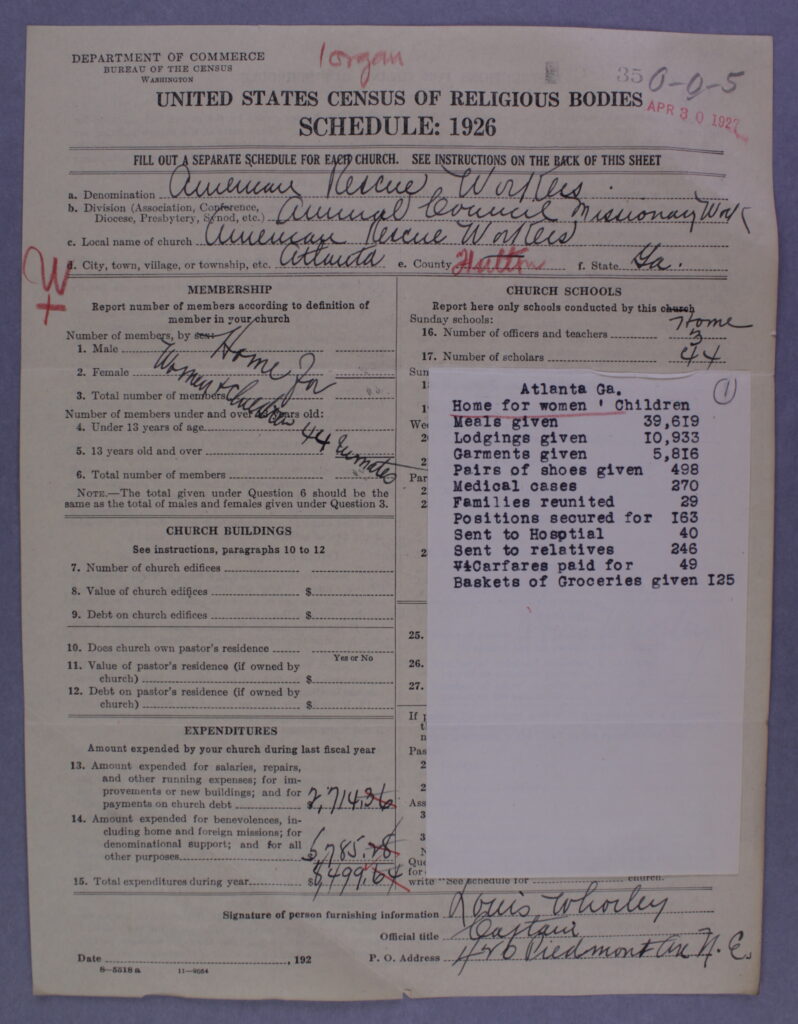

But for the American Rescue Workers—a Christian denomination centered on promoting social welfare—a single question about benevolence funds was insufficient to express the amount and variety of charitable activities undertaken by their congregations. To rectify the situation, the American Rescue Workers amended the standard Census Bureau form in order to express their priorities and record the mission work which served as the bedrock of their religious life. Over the top of the part of the form that asked for information about church schools and pastor(s), the American Rescue Workers pasted a note which detailed their commitment to charity by listing the number of meals, lodging, or baskets of groceries given out, jobs secured, and other acts of charity and social welfare. By creating their own categories for the form, the American Rescue Workers sought to signify the importance of their mission: the work the members did to help their fellow citizens.

The American Rescue Workers (ARW) emerged during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a Christian religious group characterized by a quasi-military structure and an emphasis on service and social welfare. In the 1880s the ARW split from the more prominent Salvation Army organization due to financial disputes between then national commander Thomas E. Moore and the organization’s founder William Booth regarding money sent abroad for missions. In 1884, Moore became the leader of this splinter group, which incorporated as the Salvation Army in America, and later adopted the name American Rescue Workers in 1913. Similar to the Salvation Army, the ARW maintains a military-like organizational structure; they employ both clergy (officers) and laity (soldiers) who work in the service roles proliferated by the church. Unlike the Salvation Army, however, the ARW practice the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Rooted in the Second Great Awakening and the nineteenth-century holiness movement, American Rescue Workers sought to express the love of God through tangible acts of service and therefore focused their activities on charitable work. Today, the American Rescue Workers continue this mission of service through the operation of brick and mortar and online thrift shops.

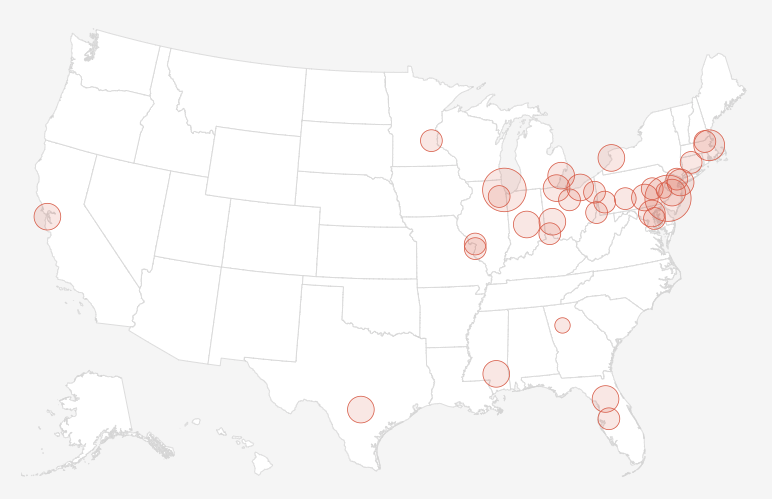

The 40 American Rescue Workers schedules included in the 1926 Census of Religious Bodies represent 97 American Rescue Workers organizations, across 35 cities, with each schedule representing between one and three different missions. In the 1920s, the American Rescue Workers were a geographically diverse organization, with missions in cities across the county—from Brooklyn, NY to San Francisco, CA, and from Hattiesburg, MS to Minneapolis, MN. However, the majority of American Rescue Workers missions were located in the midwest and mid-Atlantic. While states like Pennsylvania and Ohio had the greatest number of cities with an ARW presence, some areas like Chicago and Philadelphia had eight or nine ARW missions in one locality. Divisional headquarters were located in seven cities: Boston, MA; Buffalo, NY; Trenton, NJ; Dayton, OH; Indianapolis, IN; Chicago, IL; and Detroit, MI.

The American Rescue Workers operated many types of aid-giving organizations like missions halls, relief stations, homes for women and children, homes for men, and emergency or temporary homes. Over the course of one year the ARW nation-wide provided 157,465 meals, 35,052 garments, 551 pairs of shoes, and 47,880 lodgings while also supplying 3,028 families with groceries and 1,241 families with milk.

Although many American Rescue Worker congregations listed similar benevolent activities, some missions focused on different charitable outreach depending on need or location. For example, the American Rescue Workers in Chicago and Brooklyn focused on a specific area of need: child hunger. Schedules for these locations show that Chicago’s Food Station gave out 19,384 meals to “underfed school children” while Brooklyn operated a children’s lunch room and provided 12,171 meals. Boston aided children through a summer camp, and cities like Los Angeles, Baltimore and Quakertown, PA set up homes specifically for women and children. Other cities adapted their mission work to better fit the needs of those they were serving. Some cities like Brooklyn did not provide lodgings but instead paid rent for 13 families or individuals. Other cities like Moundsville, WV, Youngtown, OH, Toledo, OH, and Boston, MA supplemented the amount of lodgings given by providing coal for families’ heating and cooking needs. Finally, 19 cities helped with transportation difficulties by supplying 427 car-fares to people in need.

Missions also focused on needs beyond just the material. In Atlanta, the ARW concentrated on helping women and children by working to reunite families and relatives, helping people find jobs or getting medical care. In one year, Atlanta’s Home for Women and Children reunited 29 families, helped 246 people travel to the homes of relatives, aided 163 people in finding jobs, gave 270 people medical aid, and paid for 40 people’s hospital stays—in addition to providing food, shelter, clothing, and groceries.

While the social aid provided by the American Rescue Workers is impressive, they were not the only denomination who believed in the importance of charitable work; in fact, many of the churches and religious organizations recorded in the 1926 Census of Religious Bodies considered mission work and benevolent giving to be vital parts of their religious life. The centrality of mission work to American christians can be seen in the Census Bureau’s form itself. Despite including only three questions about a church’s expenditures, one question specifically inquired about the amount given by a congregation for “benevolences” and to fund “home and foreign missions.” Congregations across denominations were happy to furnish this information—when asked—and recorded benevolent expenditures ranging from hundreds to thousands of dollars per year. However, the Census Bureau’s choice of questions reveals that the US government was more concerned with the monetary value of a congregation’s social work (and how it related proportionally to the church’s overall budget) instead of the actual details of the charitable work undertaken. Nevertheless, the inclusion of benevolences within the Census Bureau’s scant list of financial questions demonstrates the importance of charity and mission work among early twentieth century churches.

Though many congregations funded charitable work, they did not go out of their way to amend the standard Census Bureau form in order to detail their efforts; they simply supplied answers to the questions that were asked. The American Rescue Workers, on the other hand, felt so strongly about their mission of serving and helping people in need that they took the time and effort to revise the schedule form, enumerate their charitable work and provide extra information that the Census Bureau had not asked for. They were the only denomination to do so. By refusing to adhere to the standard schedule form, the American Rescue Workers actively opposed the restrictive categories that the U.S. government sought to document, and instead asserted the value of their own mission and activities.

The American Rescue Workers’ decision to include detailed information about the amount and types of charity work they carried out serves as a reminder of what the schedules do and do not reveal. Because most congregations supplied only the facts and figures that the Census Bureau asked for, the information we glean from the schedules is skewed by the data interests of the Census Bureau at the time. However, because the American Rescue Workers rejected the standard Census Bureau form and adapted it to their individual denomination’s needs and values, these 40 schedules offer a unique glimpse into how American Christians carried out charity work in the early twentieth century.

Sources:

“American Rescue Workers.” Melton, J. Gordon. Encyclopedia of American religions. Gale (2003), page 267.